The Incidence of Complications Associated With Lip and/or Tongue Piercings a Systematic Review

ADOH.MS.ID.555845

Research Article

Complications of Oral and Peri-Oral Piercings Amidst Group of Females Living in Riyadh City of Saudi Arabia

AlBandary Hassan AlJameel*, Salwa Abdulrahman AlSadhan, Mashael Sulaiman AlOmran and Nassr Saleh Al-Maflehi

Department of Periodontics and Customs Dentistry, Higher of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi arabia

Submission: June 01, 2020; Published: June 08, 2020

*Corresponding author: AlBandary Hassan AlJameel, Department of Periodontics and Community Dentistry, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia

How to cite this article: AlBandary H A, Salwa A A, Mashael South A, Nassr S A-M. Complications of Oral and Peri-Oral Piercings Amongst Group of Females Living in Riyadh City of Kingdom of saudi arabia. Adv Dent & Oral Health. 2020; 12(4): 555845. DOI: x.19080/ADOH.2020.12.555845

Abstract

Background: Torso piercing, including oral & peri-oral piercing, is the exercise of puncturing specific sites of the torso to beautify them with decorative ornaments. Although such practice is common, little is known about it in Arab countries including Saudi Arabia.

Aim: Therefore, the aim of this report was to assess oral piercing related complications and the level of sensation of these complications among a group of female users of oral and peri-oral piercing living in Riyadh, Saudi arabia.

Method: To accomplish the study aim, an on-line, Standard arabic questionnaire was developed by reviewing relevant literature and was pilot tested, then it was distributed targeting females living in Riyadh, Kingdom of saudi arabia. The collected data was entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0.

Results: The results revealed that the majority of females who had oral piercings were 17-25 years of age, with the lips being the nigh reported site of oral piercing (81%), and aesthetics being the main reason (84.1%) for having the piercing. Almost 13% reported that they received their piercings from a person without professional person piercing qualification, and 57.ane% reported that they were non made enlightened of the potential risks to oral health associated with the piercing. With regards to complications, 36.5% reported discomfort, 15.nine% reported bad jiff, and 3.2% chipped teeth. In conclusion, oral piercing seems to be gaining popularity amidst Saudi population and further research is needed to meliorate understand this miracle.

Keywords:Oral piercing; Peri-oral piercing; Complications; Kingdom of saudi arabia; Cross-exclusive study

Abbreviations: PMMA: Polymethyl methacrylate; PTFE: Polytetrafluorethylene; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; HSV: Herpes simplex; EBV: Epstein-Barr viru

Introduction

Trunk piercing is the practise of puncturing specific sites of the trunk to adorn them with decorative ornaments [1]. Piercing of body parts, including the oral and peri-oral regions, was once a cultural practice having ancient origins with deep rooted religious, tribal or sexual symbolism whilst also indicating formalism hierarchies amidst members of the society [2,3]. Today, this practice has re-emerged among the youth and is gaining popularity as a course of self-expression [4]. The major contributing factors for youth choosing to pierce their bodies include a desire to exist fashionable [five]. Body piercings in the contemporary earth are too attributed to faith, traditional or occult rituals, expression of independence of the spirit, torso, and sensuality [vi,7]. It is also believed to exist a form of therapeutic healing from low which suggests that piercing maybe correlated to psychological trauma [6,vii]. Until recently body piercings were culturally restricted but due to rapid globalization and massive cross-cultural exchange through internet, television and other pop civilisation mediums, this practice has been widely adopted by different cultures. Body piercing commonly involves sites such equally the nose, earlobes, eyebrows, omphalos, nipples and occasionally, the genitals [eight]. However, it is the oral and peri-oral piercing sites that are of special interest to the dental practitioner.

Oral and peri-oral piercings generally involve sites such as the lips, natural language, cheeks, lingual and labial frenulum and the uvula or a combination of these. A needle is inserted to create an aperture through which a jewelry is then installed [v,9]. Co-ordinate to Vozza and his colleagues (2015), the tongue was the nigh commonly pierced oral site.viii Piercing jewelry comes in a broad range of shapes and sizes but the well-nigh commonly used oral piercing jewelry include the labret, barbell, captive rings and magnetic studs [ten]. A multifariousness of materials are used to industry these jewelries and include surgical stainless steel, chrome-cobalt alloys, nickel, copper, brass, niobiun, titanium, silver, 14 or 18K golden and platinum [11]. Synthetic materials like polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) and tygon are also used for making piercing jewelry as well as natural materials like bone, ivory, horn, wood and stone [12,13].

Complications of oral piercings, both local and systemic, have been extensively discussed in the literature and they can have severe health consequences [12,xiv,fifteen]. Local complications of oral and peri-oral piercing may include pain, persisting haemorrhage, nerve impairment, swelling, infection, gingival trauma, gingival recession, chipped or fractured teeth, molar sensitivity, halitosis, increased salivary flow, metal hypersensitivity, accidental aspiration of the piercing and interference with speech and swallowing [14,fifteen]. Tongue piercing, which is commonly washed at the midline just anterior to the lingual frenum may consequence in the colonization of peri-odontogenic bacteria at the pierced site in the absence of proper oral hygiene measures leading to soft tissue lesions in the tongue [13]. Delayed local complications like bifid tongue, atypical trigeminal neuralgia and hypertrophic keloid lesions are also associated with oral piercings [16]. Autonomously from these local complications, oral piercing can too lead to the transmission of blood borne viruses like man immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis (HAV, HBV, HCV), herpes simplex (HSV) and the Epstein- Barr virus (EBV) causing systemic complications.16 Furthermore, bacterial pathologies such every bit Neisseria and Streptococcus viridans induced endocarditis and Ludwig's angina have also been identified as systemic complications of oral piercing [16].

Despite being associated with a myriad of health problems, oral piercing is still popular among young people, and dental wellness-intendance professionals are facing a growing number of patients that present with oral piercings [17]. This could exist attributed to a general lack of sensation with regards to the complication of oral and peri-oral piercings [1]. Levin and colleagues [18] conducted a study on 389 immature adults and reported that 57.viii% of them were unaware of the complications related to oral piercings [18]. Similarly, a study conducted on an Italian sample of 225 teenagers establish that merely 25.3% were aware of the risk of HCV cantankerous-infection, and only 17.3% reported of cognition near run a risk of endocarditis [8]. In another study conducted in Italy, Gallè et al. [19] establish that out of the 3,868 young adults participating in the report, 84.4% knew the infectious risks associated with body piercing merely only iv.1% of them correctly identified the infectious diseases which can exist transmitted through these procedures; while 59.two% alleged that noninfectious diseases can occur later on a tattoo or a piercing, but only 5.4% of them correctly identified them [19]. These global trends require dental health-care providers to be aware of the related concerns and to be able to provide accurate data to patients considering the apply of oral piercings. While reports from around the globe assessing the sensation of people regarding complication of oral piercings are found in dental literature, no such studies have been conducted in the Kingdom of Kingdom of saudi arabia. The aim of the present study was to assess oral piercing related complications and level of awareness of these complications among female users of oral and peri-oral piercing living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The present study was a descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted on a sample of females living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Questionnaire Blueprint

A self-administered, close-ended questionnaire was created by reviewing the literature on oral and peri-oral piercings. The questionnaire was made up of 18 items. It was initially created in English and later translated into Arabic. The questionnaire was distributed among females with oral piercing living in Riyadh. An online version of the questionnaire was created and published on Google drive in order to reach a larger number of participants. The questionnaire contained items pertaining to demographic data including age, nationality, and any smoking habits, in addition to questions related to the piercing such as location, cleaning frequency, reason for having the piercing done, component and style of the jewelry, and complications related to the piercing such as molar fractures, gingival inflammation and infections. Before launching the questionnaire, information technology was pilot-tested and evaluated for clarity of diction, readability, and layout.

a) Inclusion criteria

i. Females living in the city of Riyadh who can speak, read and understand Arabic.

two. Aged in a higher place xiii years.

three. Females who already have oral and peri-oral piercings.

b) Exclusion criteria

i. Females who cannot speak, read, and understand Arabic.

2. Females having torso piercings other than oral and perioral.

Data Analysis

The participants' responses were coded, summarized, and entered into a spreadsheet software (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, SPSS 22.0, IBM.United states). Frequency distribution of participants' responses was calculated using elementary descriptive statistics and inferences were drawn.

Results

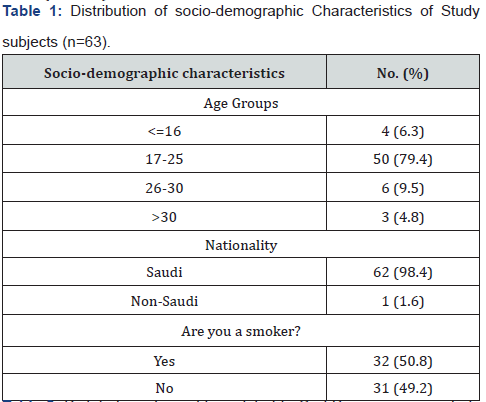

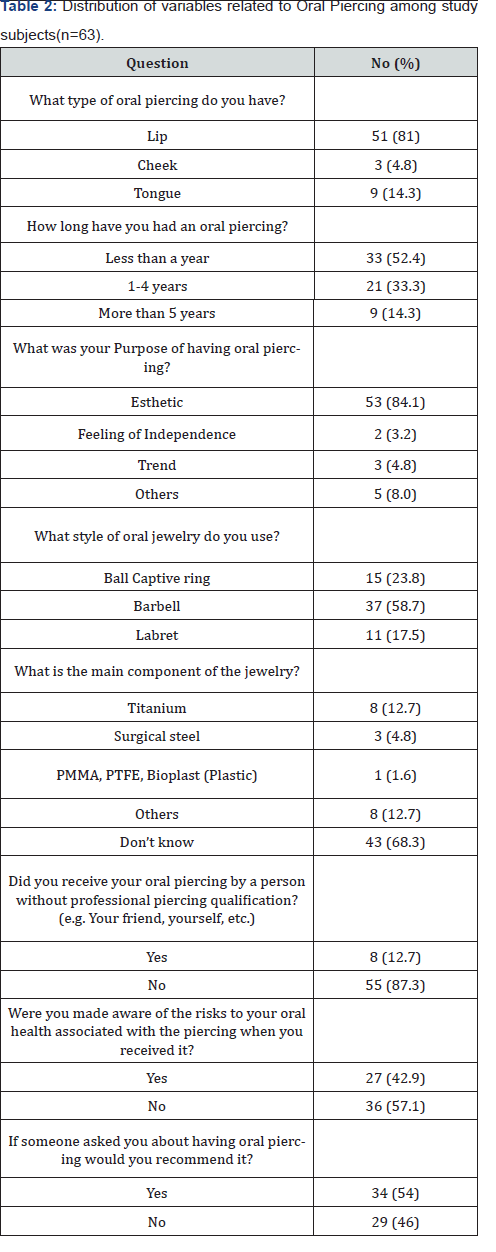

A total number of 63 participants completely filled the questionnaire. Most lxxx% of them were in the age group of 17-25 years with only half-dozen.iii% below the age of 17 years. The majority of the participants (98.4%) were Saudis, and nigh half of them (l.eight%) stated that they were smokers (Tabular array 1). As shown in Table 2, most of the study sample had lip piercings (81%), and 14.iii% had tongue piercings while only 4.8% had piercings in their cheeks. Over half of the respondents (52.4%) got their piercings washed less than a year ago while only 14.iii% accept their oral piercings for more than 4 years. When asked about purpose of getting oral piercing, over iii quarters of the respondents stated that esthetics was their principal purpose of getting it washed. Regarding the style of the piercing jewelry worn, the barbell was the well-nigh commonly blazon worn (58.7%) followed by the brawl captive ring (23.viii%). More than than ii thirds of the study sample (68.three%) were unaware of the component of their oral jewelry while amid those who did know, titanium and "others" were equal choices (12.7%). Around 90% of the respondents had their oral piercings done by a professional, and 57.1% were not made aware of potential risks associated with oral piercing. When they were asked virtually recommending piercing to someone else, almost half of the report sample (54%) stated that they would recommend others to get oral piercings washed (Table 2).

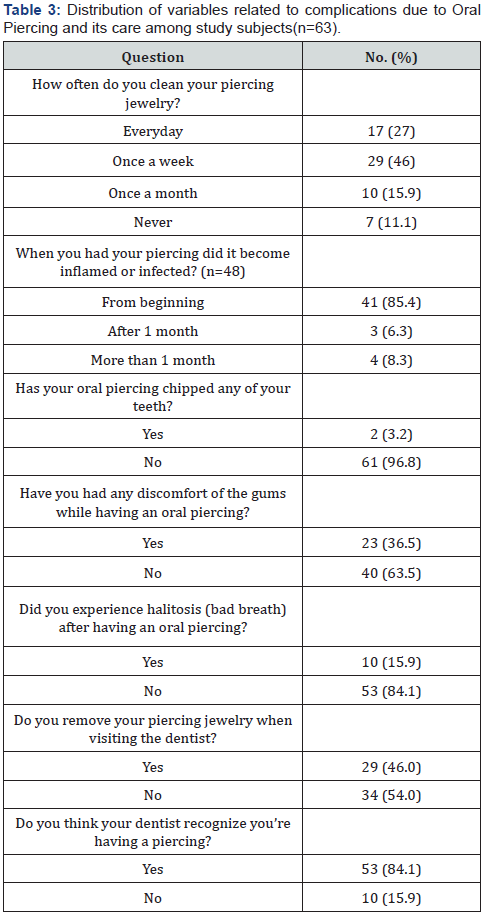

Tabular array 3 depicts information related to the oral hygiene beliefs of the participants and their awareness/experiences pertaining to complications of oral piercing. Only 27% of the participants reported that they cleaned their piercing every mean solar day, whereas 11.1% never cleaned them. With regards to the complications related to the piercing, 85.4% of the subjects had inflamed tissues around the piercings at the beginning of having them done. About 37% had discomfort in their gingival tissues, and early xv.9% experienced halitosis while having their oral piercings. Only 3.2% of the respondents stated that the piercing caused chipping of their teeth. Over half of the subjects (54%) practise non remove their piercing jewelry when visiting their dentist, and only fifteen.9% of participants think that their dentists do not recognize that they have oral piercings.

Discussion

This nowadays research aimed at assessing oral piercing related complications and level of awareness of these complications amid female users of oral and peri-oral piercing living in Riyadh, Saudi arabia. The results of this written report revealed that the bulk of the females who had oral piercings were 17-25 years of age, which indicated that such habit is common and teenagers and young adults. Also results showed that the lips seemed to exist the nearly favored site for oral piercing amid the sample. Other studies reported similar findings as the lips being the well-nigh commonly pierced site [9,20]. This could exist attributed to the fact that piercings on lips are nigh visible and more than esthetically located. Over three quarters of the participants in this report reported esthetics equally the reason for oral piercings; so, the lips seem to exist a natural option. Esthetics as the main motive for oral piercings has also been reported past another study which found that the main reason for piercings among youth is to look fashionable [5]. Studies conducted by Garcia-Pola et al. [21], Plessas & Peppalasi [22] also showed esthetics as the main reason for piercings [21,22]. This also accounts for the fact that the most commonly reported delayed complication in the current study was gingival tissue irritation which is commonly associated with lip piercings [23]. The natural language was the side by side nigh pierced site although it accounted for simply 14.two% of piercings in this study. The most common complication associated with natural language piercing is tooth chipping/cracked tooth syndrome [24]. In the present study, just three.2% of the participants stated that they suffered from chipped teeth due to oral piercing. In 2016, a systematic review conducted by Hennequin-Hoenderdos and colleagues reported that individuals with tongue piercings were more likely to experience tooth injuries than those without tongue piercings, and molar injuries were found in 37% of all observed cases in the review [23]. The lower incidence of tooth injuries in this study could be attributed to the fact that lesser number of participants in this study sample had tongue piercings every bit compared to lip piercings. With regards to the style of piercing jewelry worn, the bulk of the participants wore the barbell type. This design of oral jewelry is most frequently associated with tooth chippings and croaky tooth syndrome [xi,25,26] but this is non the only factor that determines tooth injury. Natural language jewelry, habitual biting or chewing of the device, barbell stalk length, the size of the ornamentation attached to the barbell, and the type of material used in it may all cause trauma to the teeth [27]. Hence, despite the barbell being the predominantly worn jewelry type in this study, the incidence of chipped teeth was very depression due to the fact that higher number of the participants had lip piercings every bit compared to tongue piercings which is the most commonly associated site with tooth fracture. The Clan of Professional Piercers recommend that piercing should simply exist done using biosafe materials like stainless steel or titanium, 14K gold or higher, platinum or PTFE (Teflon) [28]. Notwithstanding, studies reported that stainless steel jewelry is more prone to bacterial aggregating than jewelry made from plastics such as Teflon and recommend that wearing plastic jewelry poses less take a chance for infection than ones fabricated of metal [ii]. Information technology is important that people who want to get oral piercings washed are well-informed almost the range of materials available to choose from, and which materials are recommended that present the least threat of causing oral hard and soft tissue complications. Having a big number of respondents in our written report got their oral piercings by a piercing professional is a positive trend, however, more than half of the respondents were not fabricated enlightened of the associated risks. These findings are similar to a study conducted in Italy where 53.7% of the participants did non receive any data on risks associated with piercings from piercing professionals [eight]. This could be attributed to the fact that these piercing professionals are either not enlightened of the risks or prefer not to disembalm the risks in lodge to not scare away customers and lose business. This puts a lot of responsibility on the dentists who are visited past patients with piercings do educate them on potential risks and complications.

When hygiene habits related to oral piercings were surveyed, it was institute that less than i-third of the respondents cleaned their piercings every day. The American Dental Association recommends keeping the pierced site complimentary of nutrient debris by using a rima oris rinse after every repast. To reduce risks of oral infection after piercing procedures, pierced individuals should be advised to maintain a standard oral hygiene regimen that includes: twicedaily molar-brushing using fluoride-containing toothpaste and a soft-bristle toothbrush; regular use of floss or another interdental cleaner; and utilise of booze-free mouth rinse during and after the healing period [29]. When compared with these recommendations, the oral hygiene awareness, and practices of pierced individuals in this report are inadequate. To add to that, half of the respondents were too smokers which, coupled with inadequate cleaning of the pierced site can be the reason for halitosis beingness a complication among fifteen.nine% of the respondents. This could also easily turn into a vicious wheel equally smoking is known to be a contributing factor for plaque accumulation [xxx]. A limitation of this study was the small-scale sample size which could be attributed to cultural influences which do non encourage individuals with oral piercings to be identified and participate in surveys despite assurances of anonymity. Due to lack of previous research on this field of study in Saudi Arabia, information technology was not possible to assemble information on current local guidelines with respect to body piercings. Furthermore, it was non inside the telescopic of this research to screen the participants for blood borne diseases and found correlations with oral piercings.

Determination

Despite the limitations of this study, information technology tin be concluded that oral and peri-oral piercing is a practice that is gaining popularity among Saudi females, and esthetics is their main motivation for getting piercings. Gingival discomfort and halitosis were found to be the main complications associated with piercings in our study. The level of awareness amongst the sample regarding piercing complications and oral health practices was establish to be inadequate. At that place is also a need for farther inquiry amidst the Saudi population to include larger sample sizes and across different cities as well as to establish correlations of demographic and psycho-social factors with oral piercings and related complications locally and systemically.

Clinical Significance

Equally results indicated low level of sensation among the sample regarding piercing complications and oral wellness practices, this presents a need for dental wellness care providers to update themselves of oral wellness guidelines and complications of oral piercings so as to educate patients who present to them with piercings.

References

- Plastargias I, Sakellari D (2014) The consequences of tongue piercing on oral and periodontal tissues. ISRN dentistry 2014: 876510.

- Maspero C, Farronato G, Giannini 50, Kairyte L, Pisani L, et al. (2014) The complication of oral piercing and the function of dentist in their prevention: a literature review. Stomatologija sixteen(three): 118-124.

- Vozza I, Fusco F, Bove E, Ripari F, Corridore D, et al. (2014) Awareness of risks related to oral piercing in Italian piercers. Pilot study in Lazio Region. Annali di stomatologia v(4): 128.

- Randall JA, Sheffield D (2013) Just a personal thing? A qualitative business relationship of wellness behaviours and values associated with body piercing. Perspectives in public wellness 133(two): 110-115.

- Chimenos-Küstner E, Batlle-Travé I, Velásquez-Rengijo Due south, Garcia-Carabano T, Vinals-Iglesias H, et al. (2003) Appearance and civilisation: oral pathology associated with sure" fashions"(tattoos, piercings, etc.). Medicina oral: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Medicina Oral y de la Academia Iberoamericana de Patologia y Medicina Bucal 8(3): 197-206.

- Greif J, Hewitt W, Armstrong ML (1999) Tattooing and trunk piercing: Trunk art practices amongst college students. Clinical Nursing Research 8(4): 368-385.

- Stirn A (2003) Torso piercing: Medical consequences and psychological motivations. The Lancet 361(9364): 1205-1215.

- Vozza I, Fusco F, Corridore D, Ottolenghi L (2015) Awareness of complications and maintenance way of oral piercing in a group of adolescents and young Italian adults with intraoral piercing. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia buccal 20(4): e413.

- Hennequin‐Hoenderdos NL, Slot DE, Van der Weijden GA (2011) Complications of oral and peri‐oral piercings: a summary of example reports. International journal of dental hygiene 9(two): 101-109.

- Inchingolo F, Tatullo Thou, Abenavoli FM, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AD, et al. (2011) Oral piercing and oral diseases: a brusk time retrospective study. International journal of medical sciences 8(eight): 649-642.

- Barbería Leache E, García Naranjo AM, González Couso R, Gutiérrez González D (2006) Are the oral piercing important in the dispensary. Dental Pract 1: 45-49.

- Escudero-Castaño N, Perea-García MA, Campo-Trapero J (2008) Oral and perioral piercing complications. The open up dentistry journal 2: 133.

- Ziebolz D, Hornecker E, Mausberg RF (2009) Microbiological findings at tongue piercing sites–implications to oral health. International periodical of dental hygiene seven(4): 256-262.

- Firoozmand LM, Paschotto DR, Dias Almeida J (2009) Oral piercing complications among teenage students. Oral wellness & preventive dentistry seven(one): 77.

- Singh A, Tuli A (2012) Oral piercings and their dental implications: A mini review. Journal of investigative and clinical dentistry iii(2): 95-97.

- Oberholzer TG, George R (2010) Awareness of complications of oral piercing in a group of adolescents and young South African adults. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology 110(6): 744-747.

- Francu LL, Calin DL (2012) Lingual piercing: dental anatomical changes induced past trauma and abrasion. Romanian Journal of Functional & Clinical, Macro-& Microscopical Anatomy & of Anthropology/Revista Româna de Anatomie Functionala si Clinica, Macro si Microscopica si de Antropologie eleven(one).

- Levin L, Zadik Y, Becker T (2005) Oral and dental complications of intra‐oral piercing. Dental Traumatology 21(6): 341-343.

- Gallè F, Quaranta A, Napoli C, Di Onofrio V, Alfano V, et al. (2012) Body art practices and health risks: young adults' knowledge in two regions of southern Italy. Ann Ig 24(half-dozen): 535-542.

- Farah CS, Harmon DM (1998) Tongue piercing: case report and review of current practice. Australian Dental Journal 43(half-dozen): 387-389.

- Garcia-Pola MJ, Garcia-Martin JM, Varela-Centelles P, Bilbao-Alonso A, Cerero-Lapiedra R, et al. (2008) Oral and facial piercing: Associated complications and clinical repercussion. Quintessence international 39(1): 51-59.

- Plessas A, Pepelassi E (2012) Dental and periodontal complications of lip and tongue piercing: prevalence and influencing factors. Australian Dental Journal 57(1): 71-78.

- Hennequin‐Hoenderdos NL, Slot DE, Van der Weijden GA (2016) The incidence of complications associated with lip and/or natural language piercings: a systematic review. International periodical of dental hygiene 14(1): 62-73.

- Campbell A, Moore A, Williams E, Stephens J, Tatakis DN (2002) Tongue piercing: touch of time and barbell stalk length on lingual gingival recession and tooth chipping. Journal of periodontology 73(3): 289-297.

- De Urbiola Alís I, Viñals Iglesias H (2005) Some considerations about oral piercings. Av Odontoestomatol 21(5): 259-269.

- Peticolas T, Tilliss TS, Cantankerous-Poline GN (2000) Oral and perioral piercing: a unique class of self-expression. The journal of contemporary dental practice 1(iii): 30-46.

- Di Angelis AJ (1997) The lingual barbell: a new etiology for the cracked-tooth syndrome. Journal of the American Dental Association 128(10): 1438-1439.

- Association of Professional Piercers. Picking your piercer (2010). choosing-a-piercer.

- American Dental Association. Department of Scientific Data (2019), ADA Science Plant.

- Haffajee AD, Socransky SS (2001) Relationship of cigarette smoking to the subgingival microbiota. Journal of clinical periodontology 28(5): 377-388.

carringtonthating.blogspot.com

Source: https://juniperpublishers.com/adoh/ADOH.MS.ID.555845.php

0 Response to "The Incidence of Complications Associated With Lip and/or Tongue Piercings a Systematic Review"

Post a Comment